Meet Grace, Denise, and Sarah. At age 21, Grace is a single mother of two living in South Africa. Because her children need routine check-ups and immunizations,

Grace frequently sees pediatricians and nurses, but rarely visits doctors for her own health needs. In Namibia, 19-year-old Denise is a first-time

mother. She wants contraceptives but the few times she’s asked, the local pharmacist said they were available only for married women. And in Malawi,

18-year-old Sarah has started having sex, sometimes with male partners twice her age.

These three young women lead very different lives, but they all have one thing in common—they’re at high risk for HIV infection. Although Grace,

Denise, and Sarah are not real people, their stories illustrate diverse challenges young women face, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa, where young

women ages 15-24 are at least twice as likely to have HIV as men their age—and, in some regions, are more than eight times as likely to get infected.

IPM's Sharyn Tenn with workshop participants

IPM's Sharyn Tenn with workshop participants

Existing HIV prevention strategies are not doing enough to reduce the high rate of infection among women because women still lack a range

of options that address their diverse needs. While some women may feel comfortable discussing available HIV prevention options such as condoms with

their partners, negotiating safe sex is not a realistic option for many others, including those at risk of sexual violence. In addition, while some

women may be able to use a daily oral HIV prevention pill known as PrEP, in the three African countries where it recently become available, others

may prefer a long-acting prevention method.

The payoff for all of these tools spans far beyond individual women—evidence shows that when women are both empowered and healthy, they are more likely to have healthy families, educate their children, and make positive social

and economic contributions to society. New discreet and long-acting HIV prevention tools have the potential to empower women to protect their own health

and unlock their potential.

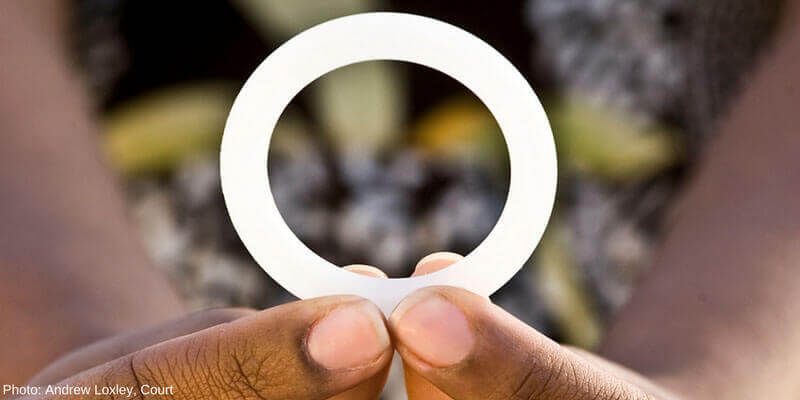

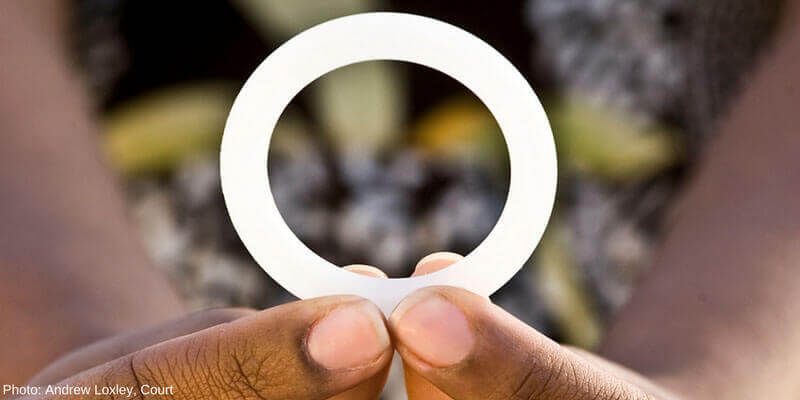

My organization, the International Partnership for Microbicides (IPM), has developed one such tool–the monthly

dapivirine ring. This flexible, silicone vaginal ring is the first long-acting, self-initiated method shown to safely help prevent new HIV infections

in women.

Results from two Phase III clinical trials last year—The Ring Study and ASPIRE—found that the ring safely reduced HIV risk among women in four African countries. Data from one study suggests that women who used the ring most consistently

saw greater risk reduction, and that the youngest women, who saw little to no protection, appeared to be the least likely to use the product. Such

adherence challenges are consistent with studies of other HIV prevention methods and underscore the urgent need to identify and overcome barriers to

product-use for young women.

The dapivirine ring. (Photo: Andrew Loxley)

The dapivirine ring. (Photo: Andrew Loxley)

IPM is committed to doing all we can to understand how to help young women who want to use new HIV prevention technologies, like the monthly dapivirine

ring, to do so consistently. Last month, we, along with AVAC, the US Agency for International Development, and Dalberg Global Development Advisors,

co-hosted an event during the United Nations Commission on the Status of Women to take a holistic view of young women’s lives. Presenters shared

examples of the ways HIV-prevention efforts can be informed by the very people who would benefit leveraging an approach called human-centered design,

which places end-users and other key stakeholders at the center of the design and implementation process. This approach is being used to create

concepts and materials to increase the adoption and sustained use of the dapivirine ring.

Several insights shared at the event could inform future steps for the dapivirine ring, should it be approved for use and added to HIV prevention programs

in sub-Saharan Africa. For example, the ring could be offered where women already regularly access health services, whether for themselves or for their

children.Doing so would make access to the ring more convenient, and subsequently, may increase its uptake. Participants also suggested that a welcoming,

environment may also help facilitate uptake as fear of judgment can be a powerful barrier to accessing and using HIV prevention products and services.

We’re encouraged by these discussions, recognizing that they are one step in a long and iterative process of getting new HIV-prevention methods into the

hands of women worldwide. Continuing to involve women in additional research on the ring and its possible introduction must continue if we are to realize

its potential and pave the way for other technologies in the pipeline such as a three-month dapivirine-only ring and a multipurpose dapivirine-contraceptive

ring. We’re currently pursuing regulatory approval for the dapivirine ring and looking to two open-label extension studies—DREAM and HOPE—currently

underway, to gain insight into when, why, and how women use the ring now that its safety and efficacy are known, and to collect extended safety data.

Expanding the toolkit of HIV prevention options available to young women would lower HIV infection rates, allow healthy women to pursue employment, and

help sustain strong and productive workforces.

The sooner we reduce the heavy HIV burden young women bear, the sooner we can empower a new generation to lead healthy and productive lives.

Sharyn Tenn is the senior director for external affairs at the International Partnership for Microbicides.