WHO in transition: What’s at risk for R&D?

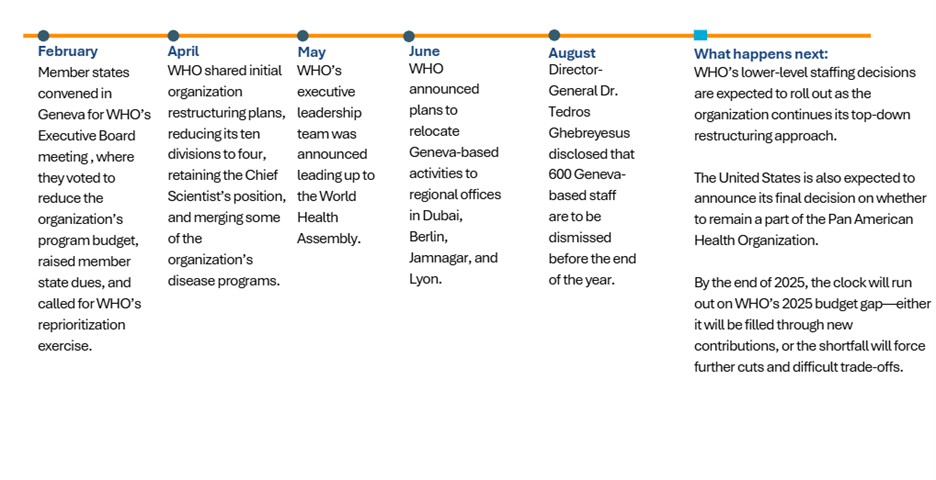

This year, triggered by a looming budget crisis and a call from member states for an assessment of the organization’s programmatic priorities, WHO has been undergoing one of its most significant shake-ups in decades. Since May, WHO has rolled out a steady stream of restructuring updates—reshaping its organizational chart, slashing budgets, cutting staff, and resetting priorities. Below, we break down what’s changed so far, what’s still to come, and why these shifts matter for the future of global health research and development (R&D).

Budget snapshot

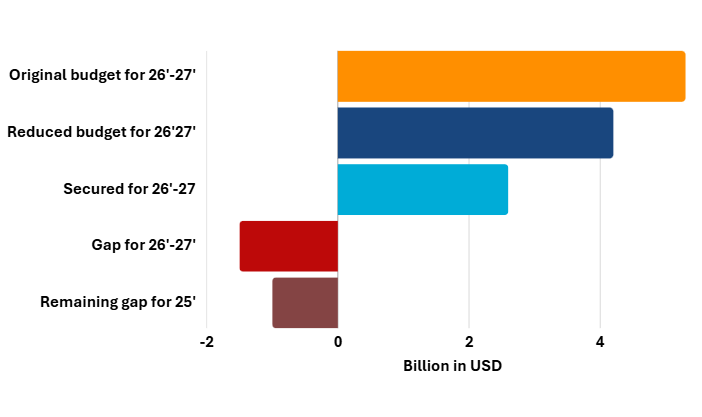

While WHO has gradually introduced reforms over the past five years, the primary driver of this year’s overhaul is its budgetary shortfalls. The organization reduced its original budget for the 2026-2027 biennium from $5.3 billion to $4.2 billion at the WHO Executive Board meeting this February, with only $2.6 billion secured so far for the revised budget.

WHO has taken steps to raise additional money, including increasing its membership dues by 20 percent for more flexible, un-earmarked funds and calling on member states for voluntary contributions through the organization’s latest Investment Round.

However, WHO still faces a $1.7 billion funding shortage to reach its $4.2 billion budget for the next biennium, and a $600 million gap to cover staff salaries through the rest of this year. This strain has been compounded by unpaid contributions from the United States following the Trump Administration’s decision to initiate US withdrawal from the organization in January 2025 and delays under the Biden Administration to pay US dues for 2024. As of this September, the United States owes the organization $260 million in member dues ($130 million for membership in 2024 and another $130 million for 2025).

These budget strains are not felt evenly across the agency. Programs tackling infectious diseases and climate and health remain relatively well-resourced, and even noncommunicable diseases—which have historically been underfunded—have seen some growth. By contrast, neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) and health emergency preparedness and response face acute shortfalls, leaving critical gaps in WHO’s ability to act where the stakes are highest.

Staffing and operation cutbacks

| Staffing cuts: WHO announced plans to reduce its global workforce by 20 percent before the end of 2025, with 425 positions cut so far and an additional 600 layoffs expected at its Geneva, Switzerland headquarters. So far, it seems that junior and mid-level technical roles have been disproportionately impacted, while more senior posts have been retained. |

| Relocations: To reduce costs associated with its Geneva headquarters, WHO has delegated a number of activities to regional and satellite offices. Health Emergencies functions are being relocated to Dubai, United Arab Emirates; laboratory surveillance to the WHO Pandemic Surveillance Hub in Berlin, Germany; the Traditional, Complementary, and Integrative Medicines unit to Jamnagar, India; and selected finance and human resources functions to WHO’s existing office in Lyon, France |

Timeline of changes

Structural changes: January vs June

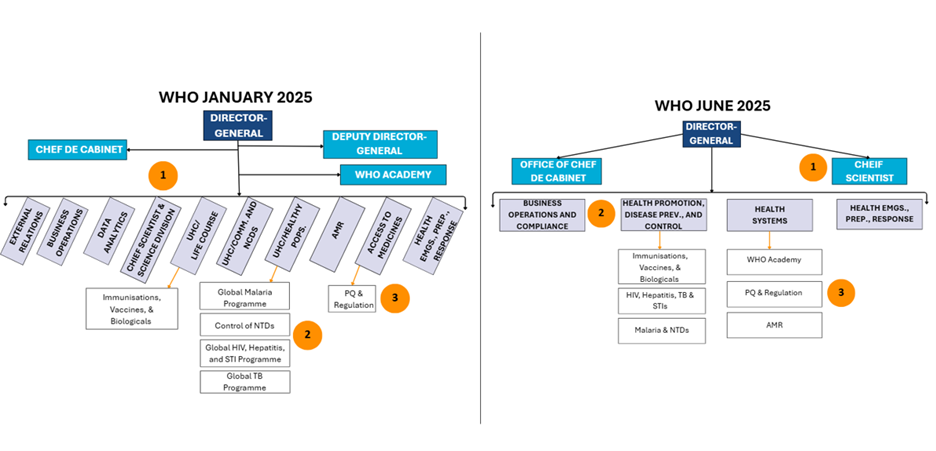

Since May, WHO has initiated a far-reaching reorganization of its leadership and program structure in response to budget shortfalls, consolidating ten offices into four broader divisions. The goal, according to WHO leadership, was to simplify reporting lines, reduce duplication, and group related programs under larger umbrellas. In this reshuffle, some of the agency’s R&D-focused programs were impacted by these structural changes, including:

| The Office of the Chief Scientist: This role was reconstituted as a leadership office, led by Dr. Sylvie Briand (succeeding Dr. Jeremy Farrar), rather than its own division, as it was in WHO’s previous structure. In its new capacity, the Chief Scientist’s office is responsible for bringing together global experts and networks working in science and innovation to guide, develop, and deliver high-quality R&D policies and services. In placing the Chief Scientist’s office at the top of its new structure, WHO may take a more top-down approach to this role, where WHO’s lead scientists will formulate directives to be carried out at the division level. The newly positioned office will also now house other R&D-relevant programs, including WHO’s Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases, a program committed to ending poverty-driven infectious diseases, though no director has yet been announced. |

| New Health Promotion, Disease Prevention, and Control division: This new division, led by Dr. Jeremy Farrar, was created by consolidating multiple former divisions, and it now covers major disease programs like HIV and Tuberculosis (TB) (merged into one), plus malaria and NTDs. Historically, the organization's HIV and TB programs have been linked, with similar strategies for prevention, diagnosis, and treatment, so these programs may benefit from the merger. Malaria and NTDs, temporarily headed by Dr. Daniel Ngamije Madandi as no official director has been named, are also now a merged program, which is likely an effort to house all vector-borne diseases in one unit. WHO’s Immunisations, Vaccines & Biologicals department, to continue to be led by Dr. Katherine O'Brien, has been largely insulated from many changes and will continue most of its major activities such as guiding immunization research and developing target product profiles (TPPs). |

| The new, expansive Health Systems division: This division, directed by Dr. Yukiko Nakatani, contains several programs, including WHO’s Prequalification (PQ) program, a new antimicrobial resistance (AMR) department, and the WHO Academy. We imagine that WHO’s PQ and AMR activities will continue relatively seamlessly under Dr. Nakatani’s divisional leadership, as she led the organization’s previous Access to Medicines division (that used to house PQ) and the organization’s AMR division, which has been downgraded to a department and is led by Dr. Yvan Hutin. The WHO Academy—the organization’s global health workforce learning center—has been combined with WHO’s Health Workforce and Nursing departments, led by Dr. David Atchoarena. |

Why this matters for R&D

WHO’s restructuring responds to urgent budget shortfalls and demands for greater efficiency. But for R&D, the stakes are too high to risk erosion, and WHO’s R&D functions must not only survive the restructuring but be fully resourced to deliver.

Core functions that require sustained investment:

- WHO’s PQ program and regulatory pathways

Leaner teams could lengthen timelines for WHO’s PQ and regulatory alignment efforts, which are crucial for low- and middle-income country access to vaccines, diagnostics, and therapeutics. Relocations and reductions in work could mean delays in products moving through review and lead to the deprioritization of some product streams, which will increase the time it takes to get products to market. - WHO’s coordinating role for international technology transfer

The organization’s role as an international coordinator for technology transfer (such as through WHO’s mRNA Technology Transfer Programme) must be prioritized in staff reductions as they are sensitive to staff continuity. Following these cuts, we could expect fewer pilots, slower vendor vetting, and tighter geographic footprints. - WHO’s surveillance and reference networks

If regional posts are eliminated, sustaining the organization’s global lab networks (e.g., the organization’s Global Influenza Surveillance and Response System and other pathogen surveillance) becomes harder, with fewer coordination nodes, slower assay validation and data sharing cadence, and more reliance on partners to fill gaps. - WHO’s R&D and clinical trial coordination platforms

WHO’s role is largely convening and coordination, and these cuts risk delays for trial start-ups, protocol maintenance, and data harmonization during outbreaks. - WHO’s emergency readiness responses

With fewer in-house experts to mobilize, it could take longer for WHO to stand up evidence reviews, trial protocols, and TPPs during outbreaks. - WHO’s role in establishing norms and standards (guidelines, evidence synthesis)

With staffing cuts, fewer technical officers and methodologists will potentially slow guideline updates, evidence reviews, and the refresh of global standards (e.g., diagnostics, surveillance). We could expect periods between scoping to recommendations, as well as narrower topic coverage as programs are prioritized.